The film follows Nick, starring James Lyons, through an emotional journey in which he attempts to save the life of his dying daughter, starring Kelly Brown, by funding a lifesaving operation. He is a successful businessman and this financial goal is easily achievable for him, until he allows the stress of his daughter’s illness to interfere with the quality of his work and he is fired from his role in the company.

From this, his life begins to spiral out of control as he uses the controversial drug trade and other illegal methods to fund his daughters operation but after becoming addicted to the substances he formerly sold, he was incapable of prioritizing his savings. His daughter ultimately passes away which results in a prolonged battle with schizophrenia and eventually the dramatic ending.

Synopsis of the Title Sequence

The main character, Nick, starring James Lyons, will be shown running in various locations. He will also be shown panicking over the voices that he can hear whilst he’s running. As Nick is running, there will be scenes which reveal the titles and will be superimposed in the editing process. At the end of the title sequence, Nick is shown contemplating shooting himself as Raoul enters the shot, and the audience feel obliged to watch the whole film to discover which character dies. At this moment, the screen will black out and the title of the film will appear on a black screen.

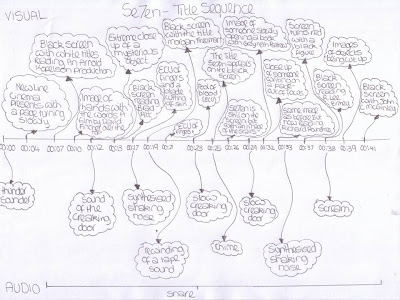

Time line

Shot List

Storyboard & technical detail

Risk Assessment

It’s important to perform a risk assessment so that we are prepared for the filming stage and making sure everyone is safe. Listing all potential hazards also ensures that everyone is aware of the dangers and also what can be done to prevent these.

Crew List

We also decided to create a crew list describing the roles of each member of the project for each scene, and any additional props or equipment that is needed.

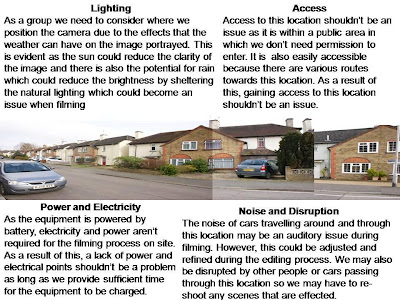

Locational and Technical Reece

In order to prepare for the filming process we photographed the locations which we were going to use as our set and later analyzed various aspects of that location and the effects that it could have on the film. This is the conclusions that we made:

#

#